"File:Bust of Cicero (1st-cent. BC) - Palazzo Nuovo - Musei Capitolini - Rome 2016.jpg" by José Luiz is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Imagine you are cruising the internet one day. You click on a story that resonates with you. It confirms all your suspicions about the world and provides a simple explanation for something that has been troubling you. Later, you click on another story that triggers intense cognitive dissonance. It makes you feel uncomfortable. If it were true, you would have to question some of your assumptions. What should you do?

Most people who are doing their own research about the world would be tempted to share the first story and click away from the second story. However, an ancient school of philosophy teaches us a very pertinent lesson. The skeptics of ancient Greece and Rome might be surprised by the internet, search engines, social media, online newspapers and memes, but once they had got over their shock their advice would be very sound: We should suspend judgement on either story, investigate further and try and work out the likelihood that either story is credible.

The Sharpen Your Axe project is based on a probabalistic approach, which we have compared to a mental app. We have described the prisoner’s dilemma and Ockham’s razor as extensions to the app. We can think of skepticism as an operating system, without which the app won’t work.

Skepticism has two founding fathers. The first was Socrates, a stoneworker who lived in Athens during an early experiment with democracy. He claimed not to know anything much and was surprised when he was described as the wisest man in the city-state. He thought there must be many people wiser than him, so set about engaging his fellow citizens in long, probing conversations. He found their worldviews tended to be contradictory and poorly considered and eventually realized that they didn’t know much either. If he was the wisest man in Athens, it was only because he was the only one who realized that he didn’t know anything.

Sadly, Socrates’ fellow citizens found his probing irritating and voted that he needed to commit suicide (although Athens was an early democracy, human rights were thousands of years in the future). He did so cheerfully. One of his students, Plato, wrote down his dialogues and probably invented some new ones as well, with a semi-fictional Socrates as the protaganist.

Plato founded the Academy after Socrates’ death. It was the ancestor of modern universities. His greatest student was Aristotles, who famously taught the Macedonian conqueror Alexander the Great. The second founding father of skepticism, Pyrrho, travelled East with Alexander’s army. He might have come across an early form of Buddhism on his travels, but the details are murky. When he returned, he taught his followers to suspend judgement.

While Socrates had triggered massive cognitive dissonance with his probing questions, Pyrrho’s approach is actually a very healthy way of handling our own sense of cognitive dissonance when we are faced with information we find troubling or exciting. Just suspend judgement on it!

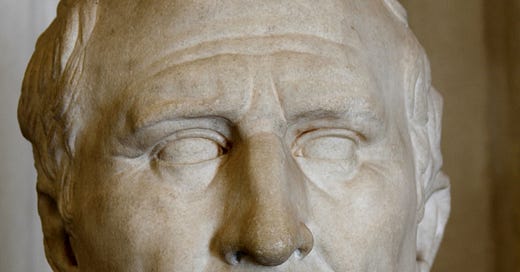

Two schools of skepticism developed in the ancient world. Academic skepticism followed Socrates, while Pyrrhonism followed Pyrrho. While they disagreed on some points, they also influenced each other. After the rise of the Roman Empire, an Academic skeptic called Cicero described an approach based on arguing against everything (Socrates) while openly judging nothing (Pyrrho). He also describes a third element: Trying to work out which idea was the most likely to be true. Sadly, scholars don’t know whether Cicero invented this major breakthough in human thought himself or if it was developed by a thinker whose name has been lost to the mists of time.

Skepticism became deeply obscure after the fall of Rome, but ancient texts from Cicero and others began to circulate during the Renaissance and the Reformation. Descartes, the founder of modern philosophy, famously struggled with skepticism. Meanwhile, the founders of the Royal Society in England - the first institution in the history of modern science - made moderate, probabilistic skepticism one of science’s founding principles.

It is important to note that skepticism offers us nothing more than uncertainty, doubt and provisional answers. People can find skeptics irritating, as Socrates discovered more than 2,400 years ago. On the other hand, utter certainty - the opposite of skepticism - can be attractive to us. This gives an advantage to gurus, professional conspiracy theorists and promoters of fringe views, even though they often have a weak methodology.

The word skepticism is often misused in modern life. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seem some people describe themselves as “lockdown skeptics.” If Cicero came back to life, he would shake his head at this use of the word - skepticism means “investigation” in ancient Greek. Of course, we need to be skeptical about whether lockdowns work or not. We also need to be skeptical of just letting the disease rip through the population. Most of all, though, we need to be skeptical about our own motivations and biases, not to mention being self-critical. Being skeptical in multiple dimensions and slowly adjusting our views to the evidence is very different from just being skeptical of one policy that we happen to dislike.

I explore skepticism in much greater depth in Chapter Nine of Sharpen Your Axe. If you missed the beginning, here are the links to Chapter One, Chapter Two, Chapter Three, Chapter Four, Chapter Five, Chapter Six, Chapter Seven and Chapter Eight. As always, if you have enjoyed this content or found it useful, I would greatly appreciate it if you could share it on social media or with others who might appreciate it. I made Sharpen Your Axe free so that the information could circulate as widely as possible and I need your help to get the word out.

Also, if you haven’t subscribed yet, please do so in order to receive future posts. The next one in a week’s time will look at how to judge the credibility of your reading material. See you then!

Update (25 April 2021)

The full beta version is available here

[Updated on 10 March 2022] Opinions expressed on Substack and Twitter are those of Rupert Cocke as an individual and do not reflect the opinions or views of the organization where he works or its subsidiaries.